If you follow me on Twitter, you may have noticed my increasingly deranged campaign to get the world to stop comparing companies based on their market capitalization. See, for example:

Where am I going with this? And what is market capitalization anyway? Market capitalization is how much the market values the equity of a company. You take the price per share, and you multiply it by the number of shares outstanding. If the ownership of your company is split into 100 shares, and the price of a share is $10, then the market is implicitly saying that the full set of 100 shares is worth $1000, which would be your market capitalization.

So why do I care if people make comparisons of companies based on these numbers? The reason is they don’t mean what most people think they mean, and the casual reliance on these figures to represent “size” is emblematic of a problem I see everywhere in statistics and data science, which is that the analysts often have very little idea what the numbers mean.

Using market cap is understandable; it seems fairly obvious that if you wanted to measure how valuable a company was, that something like market cap would make sense. The devil, though, is in the details. Specifically defining the terms “valuable” and “company”.

I’m going to start with a more approachable example. Let’s say you’re perusing a list of the most valuable homes in your neighborhood. Right off the bat it looks off to you. That waterfront mansion? The one that sold for $10 million just last month? It’s not on the list, somehow. But a few totally modest homes have made the cut. Wait… is that… your house? It is! This makes no sense! Curious as to what the hell is going on, you read the fine print.

You find out that the folks who put together the list made some strange choices in terms of how they defined “most valuable”. They didn’t use the purchase price. They used how much the current owners put down as equity. That $10 million waterfront mansion? Well it turns out that the current owner (rich, and highly creditworthy) structured a complex financial arrangement that had them putting down almost no equity to take advantage of very low interest rates. What about your house? You bought your bungalow entirely with cash. You didn’t want a mortgage. So by the list’s metric, you’ve got a more valuable house.

Of course, this makes no sense. Your house isn’t more valuable than the $10 million waterfront mansion. It’s obvious that this list is wrong, at least in the sense that the ranking is of a metric that doesn’t map to anything important in the real world.

But the methodology of this list is exactly analogous to what’s going on with market capitalization comparisons. Like companies, houses are financed with a mixture of equity (how much you put down) and debt (the mortgage). I should have said “like everything”, houses are financed with a mixture of equity and debt, because equity and debt (and variations like preferred equity, mezzanine financing, and so on) are the two components of the financing side of the balance sheet. And every operation — whether it’s a company, a house, a person, whatever — has a balance sheet, whether they’ve gone through the trouble of tallying it up or not.

On the other side of the balance sheet sit the assets. By definition, both sides must be equal (or, in balance); in fact, the fundamental accounting equation is that assets are always equal to financing, or the sum of equity and debt.

When people think about how much a house is worth, they are thinking about the asset side of the balance sheet. That is, how much the house is worth, not how much principal is outstanding on the mortgage, or how much the owner put down when they bought it. The same is true for companies. When people think of Apple, they are thinking about the intellectual property, the legacy, the brand, the amazing products, the stores, their supply chain, their workforce, and so on. They’re not thinking of the $3 billion in 3.85% notes maturing on May 4, 2043.

There is an important wrinkle to this, which is how much cash is in the assets. Keeping with the house analogy, let’s imagine that inside a modest bungalow sits $50m in cash in a safe, whose code is transferred whenever the ownership changes. Now the modest bungalow is worth $50m plus whatever the house is worth. If you were going to buy this house, how much would it cost you to buy it? Well, the owner of the house would certainly want to be compensated for the $50m inside it, so you’d have to come up with $50m (plus again the value of the house). But, once you owned the house, and the safe with the code, you’d have the $50m in the safe. So that part would net out, and all you’d actually be out is the amount that the house itself was worth.

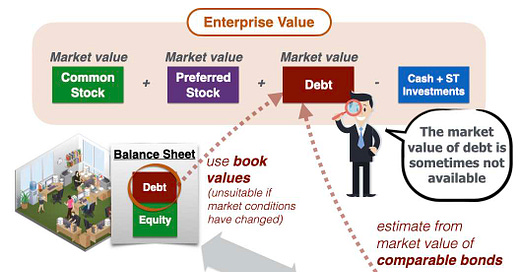

The concept of “enterprise value” was invented to answer the question: how much cash would you be out if you wanted to own all of the assets? Importantly, this number stays the same so long as the value of the (non-cash) assets stays the same.

Let’s move to an example with a company. Let’s say a company has non-cash assets (e.g. IP, property, etc.) worth $100, but no cash. There are 10 shares outstanding and no debt. The price per share then will be $10. Now, the company issues 5 shares. Since the price per share is $10, the company takes in $50 of cash.

The market cap in this example has now gone from $100 to $150. But what about the cost of buying the business? It hasn’t changed. Before it issued shares, you’d have to pony up $100 to buy all the shares; after it issued shares, you’d have to pony up $150, but you’d get $50 back, netting to $100.

What if, instead of issuing shares, the company raised $50 in debt, and used the money to buy back (and retire) 5 shares. Now the company still has $100 in assets (the cash raised was spent immediately). The price per share is still $10 (the equity holders own the $100 in assets but owe $50 in debt, so $50 in equity remains, divided by 5 shares). But there are only 5 shares outstanding. So the market cap of this company (now 5 * $10) has fallen by half. Again, what would be the cost of buying the assets? Still $100. You’d have to buy the 5 shares for $50 total, and buy the $50 of debt.

The reason that market capitalization is flawed as a metric of size is that tiny companies could be arbitrarily large, and huge companies could be arbitrarily small.

For different reasons, companies will have more or less cash on the asset side of their balance sheet, and more or less debt on the financing side. Market capitalization doesn’t care! It just mechanically rolls along, ignoring these important complications.

So what does this mean for statistics? Too often, analysts don’t get into the nitty gritty of what the numbers represent, and specifically whether or not they are invariant to irrelevant changes. Your metric for the value of a house should not change if it was financed with a 20%, or 40% down payment. Your metric for the size of a company, likewise, should not change, if they take on debt, or raise cash by issuing shares.

Quite often you see something like this in geographic data. People plot how statistics vary across place, only to have someone point out that, effectively, they’ve just mapped population density.

If you were to try to figure out where the most die-hard yoga fans in the US were, and used density of yoga studies as a proxy, you’d simply get back population density as your result. The metric you’re using doesn’t mean what you think it means.

Or, statistics about Covid death rates often just tell you how old a population is. Median age by state in the US varies by 10 years, and different quantiles may vary more than that.

The upshot of all of this is that whenever you have a metric, you have to play out in your mind what it’s measuring, what complications may exist, and whether or not it would be different if you were to change some underlying fact that’s irrelevant to your analysis. Too infrequently, analysts unquestioningly just “throw in” data. Don’t be that analyst.

perfectly explained